|

Acton Memorial Library |

Passage of the Acton Veteran Bounty Bill

The Boston Globe, June 30, 1887

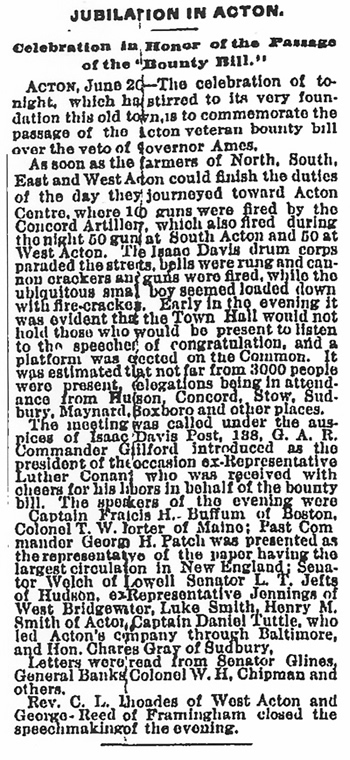

JUBILATION IN ACTON

———

Celebration in Honor of the Passage of the “Bounty Bill.”

ACTON, June 20—The celebration of tonight, which has stirred to its very foundation this old town, is to commemorate the passage of the Acton veteran bounty bill¹ over the veto of governor Ames.

As soon as the farmers of North, South, East and West Acton could finish the duties of the day they journeyed toward Acton Centre, where 100 guns were fired by the Concord Artillery, which also fired during the night 50 guns at South Acton and 50 at West Acton. The Isaac Davis drum corps paraded the streets, bells were rung and cannon crackers and guuns were fired, while the ubiquitous small boy seemed loaded down with fire-crackers. Early in the evening it was evident that the Town Hall would not hold those who would be present to listen to the speeches of congratulation, and a platform was erected on the Common. It was estimated that not far from 3000 people were present. delegations being in attendance from Hudson, Concord, Stow, Sudbury, Maynard, Boxboro and other places.

The meeting was called under the auspices of Isaac Davis Post, 138, G. A. R. Commander Guilford introduced as the president of the occasion ex-Representative Luther Conant who was received with cheers for his labors in behalf of the bounty bill. The speakers of the evening were Captain Francis H. Buffum of Boston, Colonel T. W. Porter of Maine; Past Commander George H. Patch was presented as the representative of the paper having the largest curculation in New England; Senator Welch of Lowell, Senator L. T. Jefts of Hudson, ex-Representative Jennings of West Bridgewater, Luke Smith, Henry M. Smith of Acton, Captain Daniel Tuttle, who led Acton's company through Baltimore, and Hon. Charles Gray of Sudbury.

Letters were read from Senator Glines, General Banks, Colonel W. H. Chipman [sic] and others.

Rev. C. L. Rhoades of West Acton and George

Reed² of Framingham closed the speechmaking of the evening.

- Footnotes:

- 1 — At the start of the Civil War, men enlisted without any expectation of financial reward. As the war dragged on, some towns had difficulty meeting the quota of enlistments asked for by the State. Various towns, in order to meet their quota, offered monetary rewards, or “bounties” to induce men to enlist to the credit of the town's quota. The men who responded to this inducement were not necessarily citizens of the town offering the bounty. In some cases, potential recruits “shopped around” to see who was offering the highest amount. Some men made a practice of “bounty jumping” by enlisting long enough to collect the bounty, only to then desert and enlist again under another name to the credit of some other town. It was also not uncommon for towns to pay bounties for men who enlisted to their credit in the field. John Smith, for example, a deserter from the Confederate 9th Mississippi Regiment, was credited to Acton and paid a bounty of $25 when he joined Company E of the 26th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry at New Orleans on September 23, 1862. While John Smith had received a bounty for joining the 26th M.V.I., most of the men of Company E that he served with through the rest of the War had volunteered without inducement immediately after returning home with the Davis Guards in August of 1861. After the War, veterans who had volunteered in the days before the bounty system was introduced, lobbied for some sort of compensation to redress what they perceived as an inequity. The Resolve that was eventually passed in 1887 awarded $125 from the state treasury to 31 soldiers of the 26th Massachusetts Regiment who had re-enlisted as veterans in 1863 to the credit of Acton and had never received a bounty for re-enlistment.

-

- 2 — George Reed went through Baltimore with the Davis Guards and wrote home the next day of their “little brush at Baltimore.”